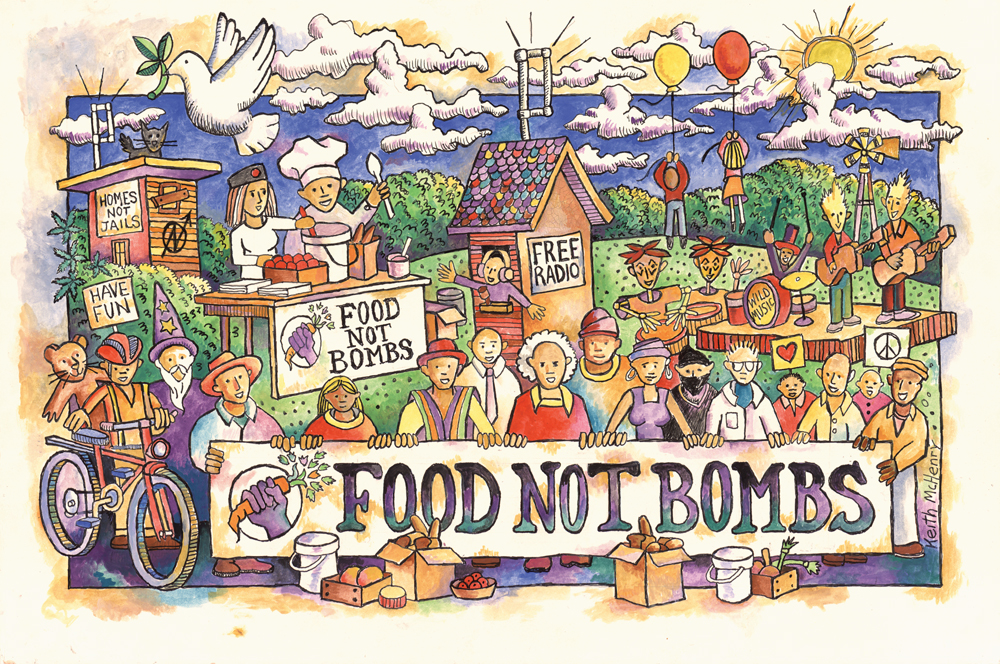

Make food not war

Two years ago, I had the sad privilege of returning to Greece after 13 years of study around Europe and Asia. I went home because I could sense that change was coming, and I had an interest in the social reform that was being caused by the economic crisis. I was frustrated with the stereotypes I kept hearing about my country. The media reported gloomy pictures from Greece. Riots, political corruption, and economic inefficiency – ‘those lousy, lazy, ouzo drinking, zorba dancing Greeks… Punish them!’

I was 30 years old, and I felt strongly that my generation was not to be blamed for the economic crisis. The Greece of my home, the Greece that I knew and loved, was a very different place to the one being portrayed in the media. I knew a society of solidarity, of collaboration, of innovation and youth.

I returned home and took over the management of the ancient olive grove belonging to my family. I convinced my recently retired parents to follow new, organic cultivation methods, and we started to exchange our knowledge with those around us. My mother explained to me how my grandfather took care of the ancient trees, and I taught her the science behind each step of the process.

I was convinced that returning to the land was one of the very few ways out of the economic crisis, and I wanted to inspire more young people to follow this example. Working together with the Youth Food Movement and Slow Food Youth Network, we convinced the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture to support the production of a short documentary series “Farming on Crisis?” We aimed to profile the innovative stories of young farmers, all over Greece, who were returning to the land of their ancestors in order to find a way out of the pervasive unemployment. We aimed to bring people a vision of Greece that was not being reported in the media, and to send a message to our young people that a solution exists! It may not be an easy one, but it does exist.

In the last few months, my country has seen a lot of things that we could not have imagined a few years ago: raw violence, the repression of individual freedoms; homelessness; suicides; children going hungry at school; hospitals and schools closing; youth unemployment rising to 63%. Our politicians are proving weak, fascism is returning, and public television has been closed down – a situation not seen since the days of our last dictatorship. So many things have changed since the beginning of 2013 that you could say the situation is spinning out of control.

The political decision by the EU to adopt the current economic ‘rescue-plan’ for Greece was made in a rush, under huge international pressure, to prevent the global economic marketplace from going into meltdown. What an irony for the country that invented the marketplace. ‘The Agora’ was a place that was both a market, and a place of intellectual exchange. People competed in body, mind and spirit, in order to exercise themselves, to contribute to society. Through participation, they contributed to ‘demos’ and created democracy. Those that did not participate were ’idiots’ – a word that stems from ’idio’ which means ‘self-secluded,’ or not participating in public issues. This is pretty much how the current political system and the consumerist economy wants us to be – it wants us to be idle, to be passive.

Civil unrest is on the rise. In Istanbul, Taksim Square and Gezi Park have become symbols of a people striving towards freedom. In the streets of Rio de Janeiro, youth are protesting against large scale spending on mega projects, aimed solely at serving corporate interests. Incapable of engaging in a serious dialogue with society, governments are increasingly using violence and chemicals against their own citizens, often considering them as ‘terrorists.’ These images are all too familiar to us in Greece; evidence that we are experiencing a period of significant unrest and potential change across the globe. The responses from government, signs that we are experiencing fundamental problems with our idea of democracy.

As the foundations of our societies become unstable, the question of whether or not we can tackle greater challenges, such as climate change, food security and resource scarcity, is in doubt. The possibility of a sustainable future will continue to diminish, unless citizens can regain a sense of control and dignity over their future livelihoods.

In this complex situation, it is my opinion, that food and farming still provide options for ‘angry youth,’ creating tangible opportunities for work, and a future. In Greece, the crisis is driving us to rediscover the assets of our countryside and food culture. Furthermore, food production is something we can take control of; we can get on with it, in spite of government policies that focus on austerity rather than growth.

The economic crisis represents an opportunity, a new era of growth and possibility for a grass roots food movement. This is something more than a new age, environmentalist trend, rather a notion that could unite people from all walks of life, no matter how different our identities. Putting our hands in the dirt provides a peaceful alternative to rioting in the streets. Building, creating, and making, restores our sense of dignity, helps us to build community, and shows us a way out of the crisis.

In an ideal world, we would have governments and politicians that recognise the importance of creating rather than destroying, building instead of dismantling, supporting instead of suppressing, but in the absence of sense, a grass roots food movement is one of the few things that we can carry on building for ourselves.

Originally published on the Sustainable Food Trust.